Show the package imports

import random

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pdACTL3143 & ACTL5111 Deep Learning for Actuaries

import random

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

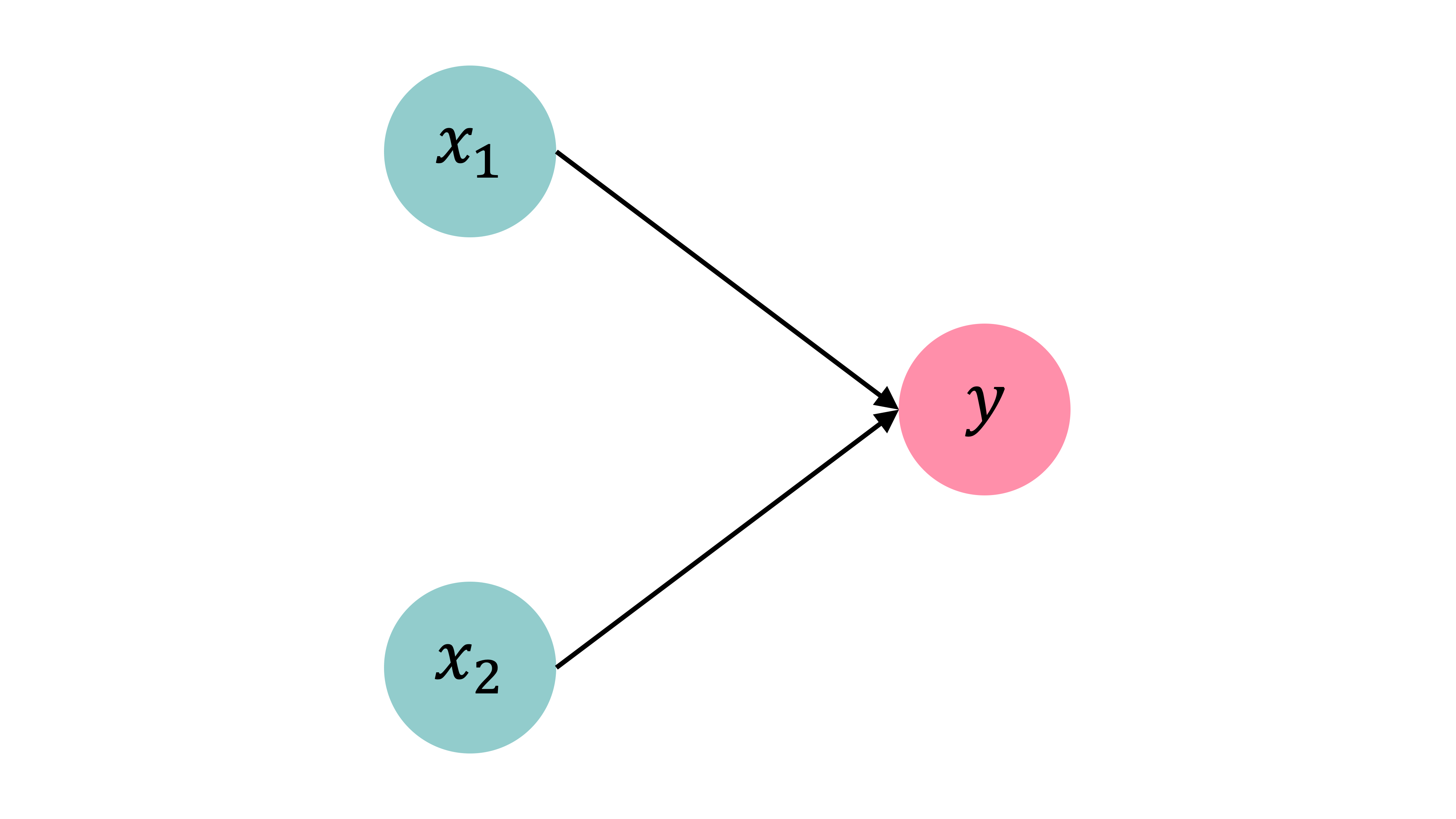

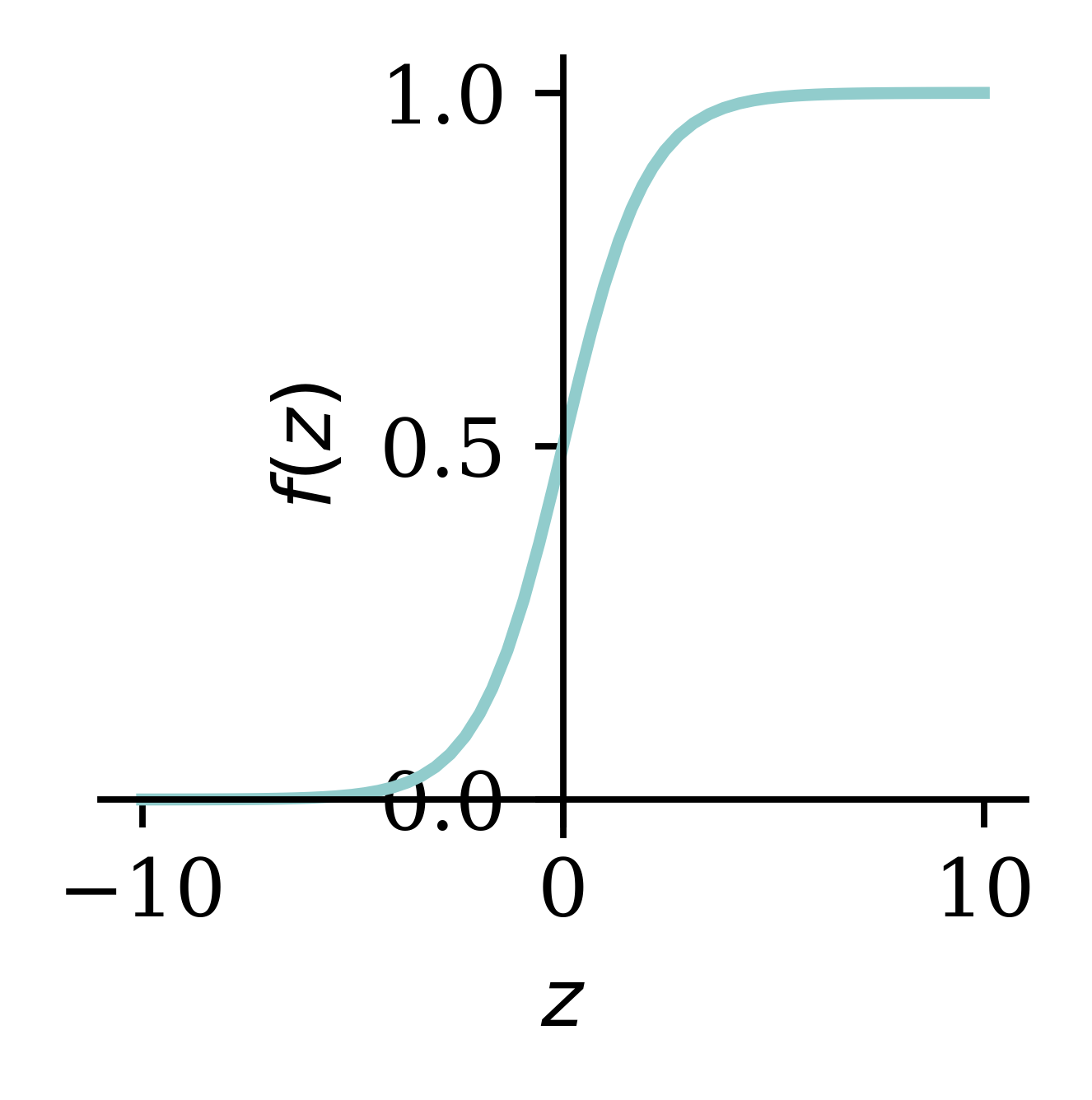

import pandas as pdIf we want to solve a binary classification problem, we can fit a logistic regression. We could say that a logistic regression is a neural network with no hidden layers and 1 neuron. z_i is a linear combination of the covariates for observation i. The activation function is \sigma(\cdot) which converts the z_i to a value y_i between 0 and 1, representing the probability of a positive outcome. The sigmoid activation function is the inverse logit function.

Observations: \mathbf{x}_{i,\bullet} \in \mathbb{R}^{2}.

Target: y_i \in \{0, 1\}.

Predict: \hat{y}_i = \mathbb{P}(Y_i = 1).

The model

For \mathbf{x}_{i,\bullet} = (x_{i,1}, x_{i,2}): z_i = x_{i,1} w_1 + x_{i,2} w_2 + b

\hat{y}_i = \sigma(z_i) = \frac{1}{1 + \mathrm{e}^{-z_i}} .

x = np.linspace(-10, 10, 100)

y = 1/(1 + np.exp(-x))

plt.plot(x, y);

When we have multiple observations, we can manually calculate the predicted values using the fitted weights and biases.

data = pd.DataFrame({"x_1": [1, 3, 5], "x_2": [2, 4, 6], "y": [0, 1, 1]})

data| x_1 | x_2 | y | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 |

| 2 | 5 | 6 | 1 |

Let w_1 = 1, w_2 = 2 and b = -10.

w_1 = 1; w_2 = 2; b = -10

data["x_1"] * w_1 + data["x_2"] * w_2 + b 0 -5

1 1

2 7

dtype: int64Now let’s consider this in matrix notation. \mathbf{X} is the matrix of covariates, \mathbf{w} is the column vector of weights, b is a constant and \mathbf{z} is the output column vector before activation. Finally, \mathbf{a} is the output column vector after applying the activation function. Note that:

Have \mathbf{X} \in \mathbb{R}^{3 \times 2}.

X_df = data[["x_1", "x_2"]]

X = X_df.to_numpy()

Xarray([[1, 2],

[3, 4],

[5, 6]])Let \mathbf{w} = (w_1, w_2)^\top \in \mathbb{R}^{2 \times 1}.

w = np.array([[1], [2]])

warray([[1],

[2]])\mathbf{z} = \mathbf{X} \mathbf{w} + b , \quad \mathbf{a} = \sigma(\mathbf{z})

z = X.dot(w) + b

zarray([[-5],

[ 1],

[ 7]])1 / (1 + np.exp(-z))array([[0.01],

[0.73],

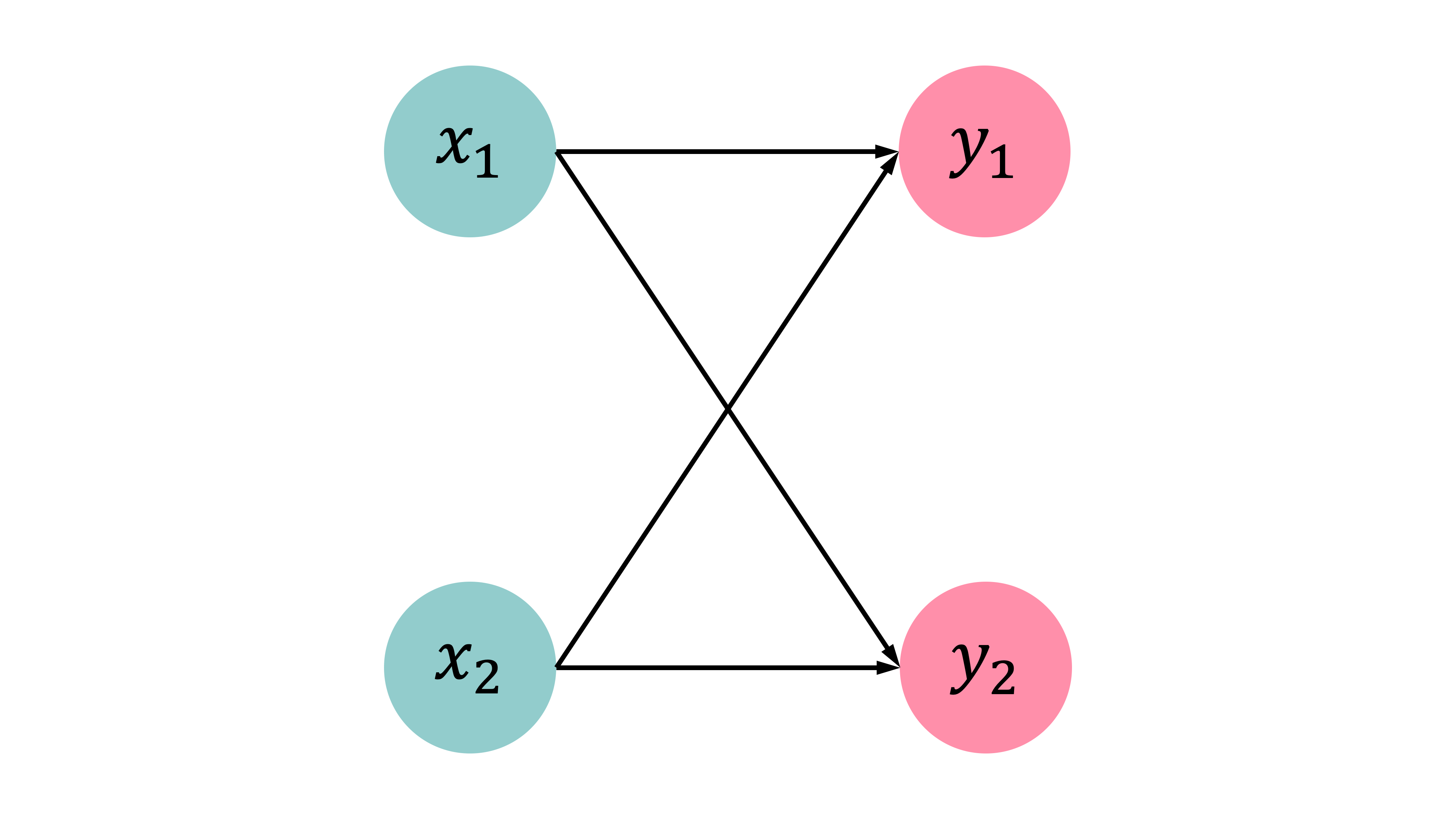

[1. ]])This time, our problem is still a logistic regression problem, but with a softmax output. There are 2 neurons, each representing the probability that the target is in either category. In the context of matrices, this means that the output is a vector rather than a single value. Separate weights and biases are fitted for each neuron. The activation function is no longer sigmoid, but softmax. The predictions are converted to probability distributions.

Observations: \mathbf{x}_{i,\bullet} \in \mathbb{R}^{2}. Predict: \hat{y}_{i,j} = \mathbb{P}(Y_i = j).

Target: \mathbf{y}_{i,\bullet} \in \{(1, 0), (0, 1)\}.

The model: For \mathbf{x}_{i,\bullet} = (x_{i,1}, x_{i,2}) \begin{aligned} z_{i,1} &= x_{i,1} w_{1,1} + x_{i,2} w_{2,1} + b_1 , \\ z_{i,2} &= x_{i,1} w_{1,2} + x_{i,2} w_{2,2} + b_2 . \end{aligned}

\begin{aligned} \hat{y}_{i,1} &= \text{Softmax}_1(\mathbf{z}_i) = \frac{\mathrm{e}^{z_{i,1}}}{\mathrm{e}^{z_{i,1}} + \mathrm{e}^{z_{i,2}}} , \\ \hat{y}_{i,2} &= \text{Softmax}_2(\mathbf{z}_i) = \frac{\mathrm{e}^{z_{i,2}}}{\mathrm{e}^{z_{i,1}} + \mathrm{e}^{z_{i,2}}} . \end{aligned}

data| x_1 | x_2 | y_1 | y_2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 1 |

Choose:

w_{1,1} = 1, w_{2,1} = 2,

w_{1,2} = 3, w_{2,2} = 4, and

b_1 = -10, b_2 = -20.

w_11 = 1; w_21 = 2; b_1 = -10

w_12 = 3; w_22 = 4; b_2 = -20

data["x_1"] * w_11 + data["x_2"] * w_21 + b_10 -5

1 1

2 7

dtype: int64Have \mathbf{X} \in \mathbb{R}^{3 \times 2}.

Xarray([[1, 2],

[3, 4],

[5, 6]])\mathbf{W}\in \mathbb{R}^{2\times2}, \mathbf{b}\in \mathbb{R}^{2}

W = np.array([[1, 3], [2, 4]])

b = np.array([-10, -20])

display(W); barray([[1, 3],

[2, 4]])array([-10, -20])\mathbf{Z} = \mathbf{X} \mathbf{W} + \mathbf{b} , \quad \mathbf{A} = \text{Softmax}(\mathbf{Z}) .

Z = X @ W + b

Zarray([[-5, -9],

[ 1, 5],

[ 7, 19]])np.exp(Z) / np.sum(np.exp(Z),

axis=1, keepdims=True)array([[9.82e-01, 1.80e-02],

[1.80e-02, 9.82e-01],

[6.14e-06, 1.00e+00]])In-class demo

Called batch gradient descent.

for i in range(num_epochs):

gradient = evaluate_gradient(loss_function, data, weights)

weights = weights - learning_rate * gradientBatch gradient descent tries to improve all of the predictions in one go by using the entire training set at once.

For each epoch of the data, evaluate the gradient of the loss function on the entire training set with the chosen weights. The new weights are rebalanced based on the learning rate and in the negative direction of the gradient.

Called stochastic gradient descent.

for i in range(num_epochs):

rnd.shuffle(data)

for example in data:

gradient = evaluate_gradient(loss_function, example, weights)

weights = weights - learning_rate * gradientRather than trying to improve all predictions at once, stochastic gradient descent tries to improve each observation one by one (chosen at random). The weights are adjusted many times in a single epoch.

Called mini-batch gradient descent.

for i in range(num_epochs):

rnd.shuffle(data)

for b in range(num_batches):

batch = data[b * batch_size : (b + 1) * batch_size]

gradient = evaluate_gradient(loss_function, batch, weights)

weights = weights - learning_rate * gradientSomewhere in between batch gradient descent and stochastic gradient descent, mini-batch gradient descent tries to improve batches of the training data at a time. The weights are adjusted a few times in a single epoch.

This is the most common method.

Most NNs opt for mini-batch gradient descent.

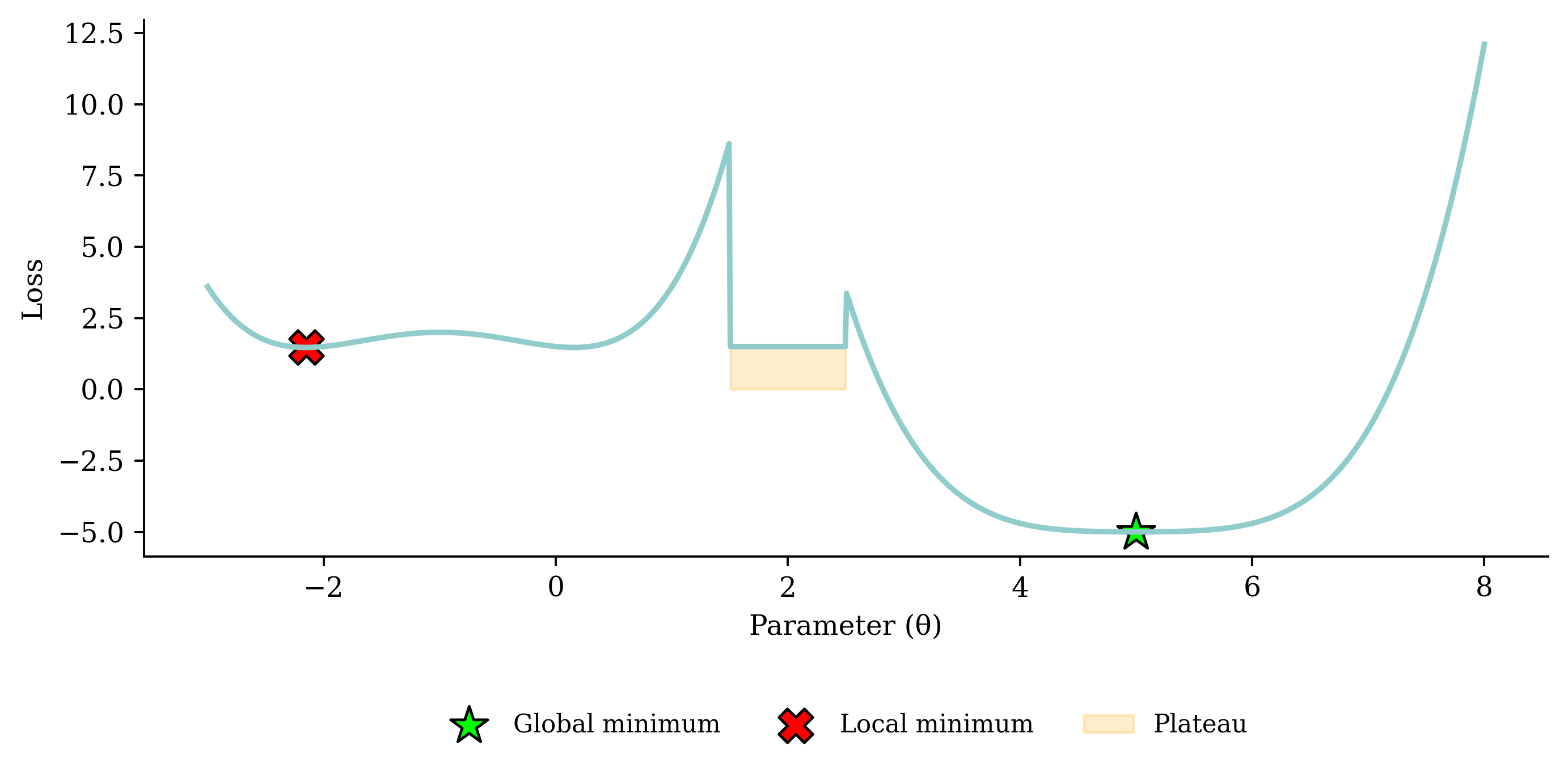

Why?

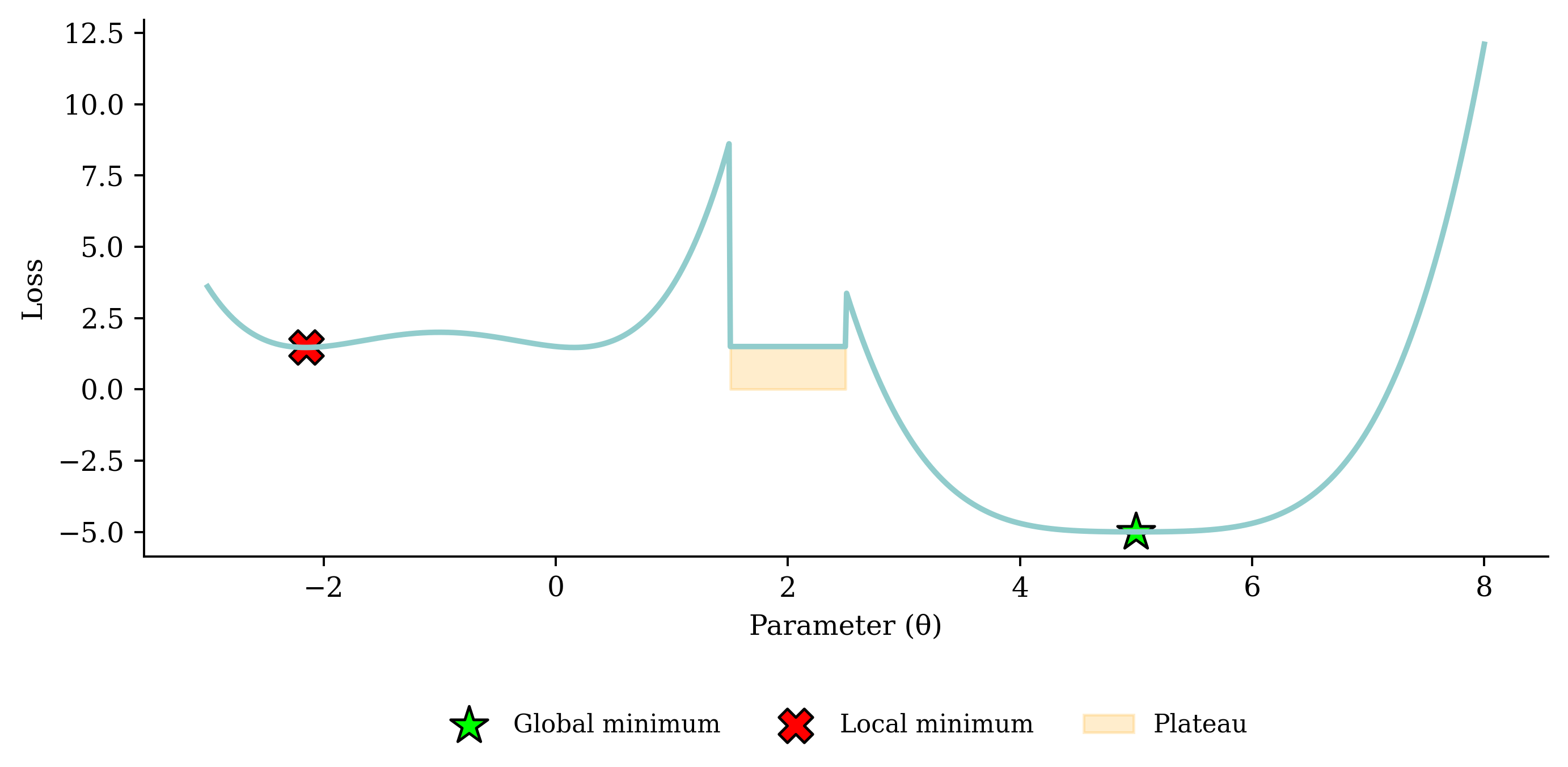

Noisy gradient means we might jump out of a local minimum.

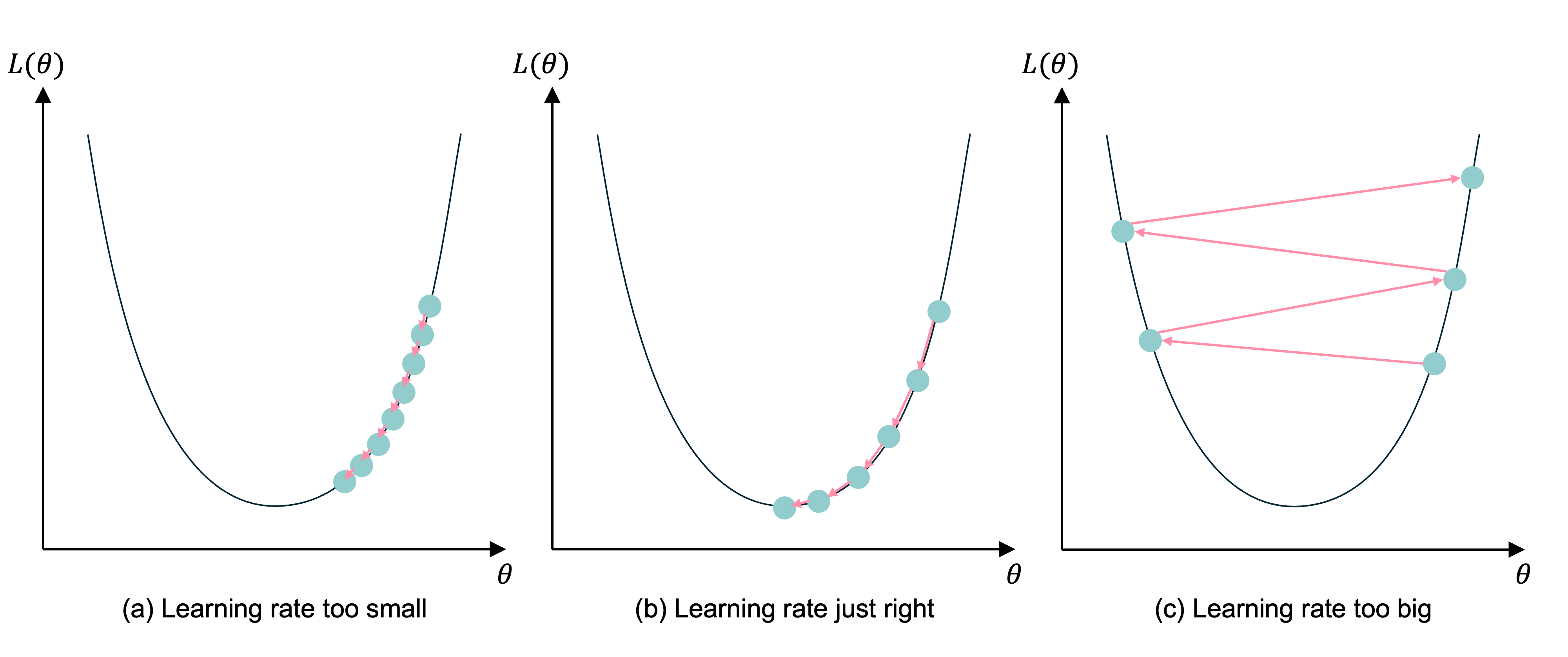

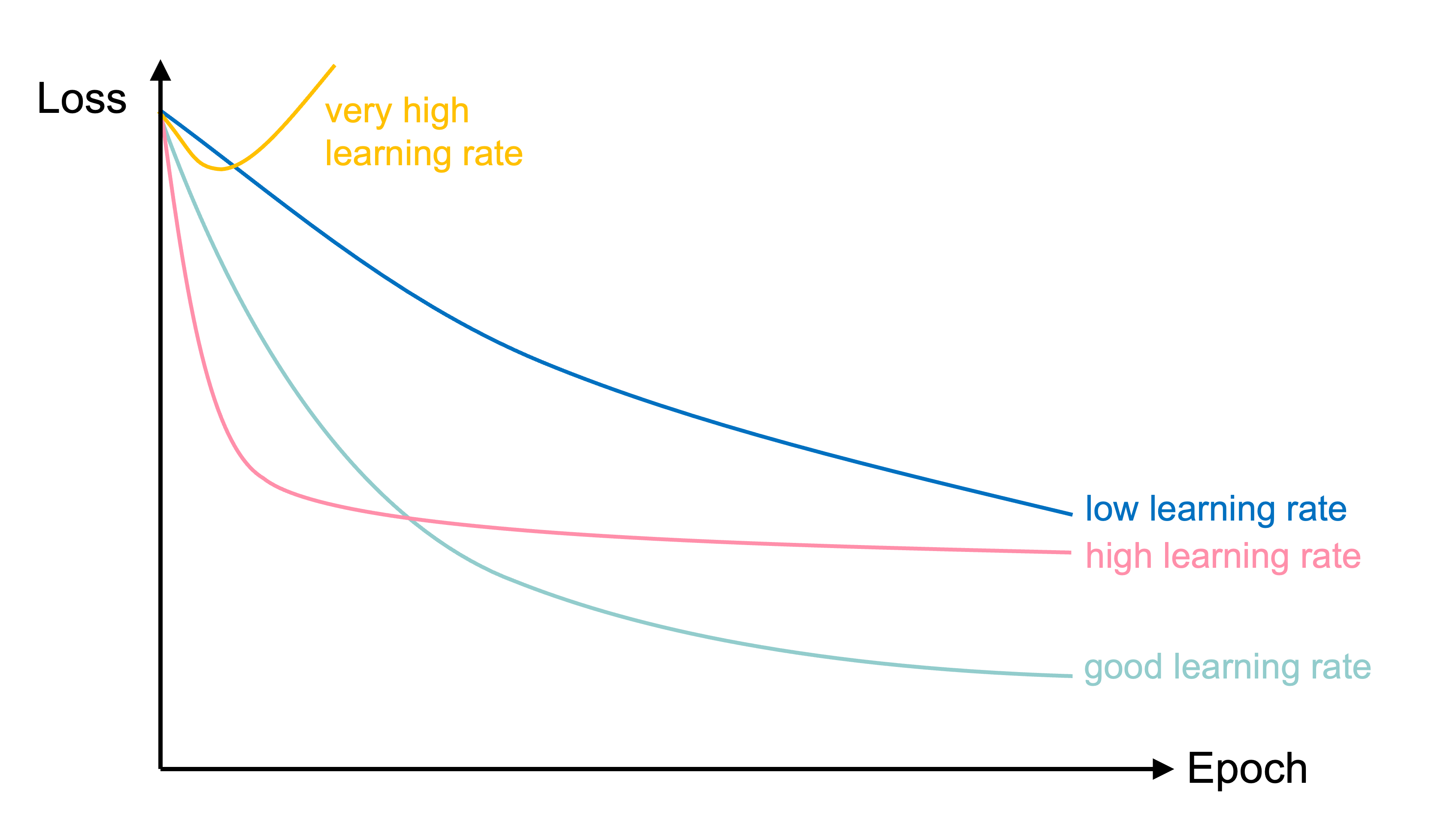

If the learning rate is too small, the subsequent NNs are too similar and it takes too long for the parameters to converge (and more likely to a local, not global, minimum). If the learning rate is too big, you could overshoot and the loss may increase.

“a nice way to see how the learning rate affects Stochastic Gradient Descent. we can use SGD to control a robot arm - minimizing the distance to the target as a function of the angles θᵢ. Too low a learning rate gives slow inefficient learning, too high and we see instability”

In training the learning rate may be tweaked manually.

How does gradient descent work mathematically?

\hat{y}(x) = w x + b

For some observation \{ x_i, y_i \}, the squared error loss is

\text{Loss}_i = (\hat{y}(x_i) - y_i)^2

For a batch of the first n observations the MSE loss is

\text{Loss}_{1:n} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n (\hat{y}(x_i) - y_i)^2

Since \hat{y}(x) = w x + b,

\frac{\partial \hat{y}(x)}{\partial w} = x \text{ and } \frac{\partial \hat{y}(x)}{\partial b} = 1 .

As \text{Loss}_i = (\hat{y}(x_i) - y_i)^2, we know \frac{\partial \text{Loss}_i}{\partial \hat{y}(x_i) } = 2 (\hat{y}(x_i) - y_i) .

\frac{\partial \text{Loss}_i}{\partial \hat{y}(x_i) } = 2 (\hat{y}(x_i) - y_i), \,\, \frac{\partial \hat{y}(x)}{\partial w} = x , \, \text{ and } \, \frac{\partial \hat{y}(x)}{\partial b} = 1 .

Putting this together, we have

\frac{\partial \text{Loss}_i}{\partial w} = \frac{\partial \text{Loss}_i}{\partial \hat{y}(x_i) } \times \frac{\partial \hat{y}(x_i)}{\partial w} = 2 (\hat{y}(x_i) - y_i) \, x_i

and \frac{\partial \text{Loss}_i}{\partial b} = \frac{\partial \text{Loss}_i}{\partial \hat{y}(x_i) } \times \frac{\partial \hat{y}(x_i)}{\partial b} = 2 (\hat{y}(x_i) - y_i) .

At all points in the neural network, we can’t have any derivative equal to 0. If it is 0 at any point, it becomes impossible for the model to learn.

This is why can’t use accuracy as the loss function for classification.

Also why we can have the dead ReLU problem.

Start with \boldsymbol{\theta}_0 = (w, b)^\top = (0, 0)^\top.

Randomly pick i=5, say x_i = 5 and y_i = 5.

\hat{y}(x_i) = 0 \times 5 + 0 = 0 \Rightarrow \text{Loss}_i = (0 - 5)^2 = 25.

The partial derivatives are \begin{aligned} \frac{\partial \text{Loss}_i}{\partial w} &= 2 (\hat{y}(x_i) - y_i) \, x_i = 2 \cdot (0 - 5) \cdot 5 = -50, \text{ and} \\ \frac{\partial \text{Loss}_i}{\partial b} &= 2 (0 - 5) = - 10. \end{aligned} The gradient is \nabla \text{Loss}_i = (-50, -10)^\top.

Start with \boldsymbol{\theta}_0 = (w, b)^\top = (0, 0)^\top.

Randomly pick i=5, say x_i = 5 and y_i = 5.

The gradient is \nabla \text{Loss}_i = (-50, -10)^\top.

Use learning rate \eta = 0.01 to update \begin{aligned} \boldsymbol{\theta}_1 &= \boldsymbol{\theta}_0 - \eta \nabla \text{Loss}_i \\ &= \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} - 0.01 \begin{pmatrix} -50 \\ -10 \end{pmatrix} \\ &= \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} + \begin{pmatrix} 0.5 \\ 0.1 \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 0.5 \\ 0.1 \end{pmatrix}. \end{aligned}

Start with \boldsymbol{\theta}_1 = (w, b)^\top = (0.5, 0.1)^\top.

Randomly pick i=9, say x_i = 9 and y_i = 17.

The gradient is \nabla \text{Loss}_i = (-223.2, -24.8)^\top.

Use learning rate \eta = 0.01 to update \begin{aligned} \boldsymbol{\theta}_2 &= \boldsymbol{\theta}_1 - \eta \nabla \text{Loss}_i \\ &= \begin{pmatrix} 0.5 \\ 0.1 \end{pmatrix} - 0.01 \begin{pmatrix} -223.2 \\ -24.8 \end{pmatrix} \\ &= \begin{pmatrix} 0.5 \\ 0.1 \end{pmatrix} + \begin{pmatrix} 2.232 \\ 0.248 \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 2.732 \\ 0.348 \end{pmatrix}. \end{aligned}

For the first n observations \text{Loss}_{1:n} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \text{Loss}_i so

\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial \text{Loss}_{1:n}}{\partial w} &= \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{\partial \text{Loss}_{i}}{\partial w} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{\partial \text{Loss}_{i}}{\hat{y}(x_i)} \frac{\partial \hat{y}(x_i)}{\partial w} \\ &= \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n 2 (\hat{y}(x_i) - y_i) \, x_i . \end{aligned}

\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial \text{Loss}_{1:n}}{\partial b} &= \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{\partial \text{Loss}_{i}}{\partial b} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{\partial \text{Loss}_{i}}{\hat{y}(x_i)} \frac{\partial \hat{y}(x_i)}{\partial b} \\ &= \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n 2 (\hat{y}(x_i) - y_i) . \end{aligned}

| x | y | y_hat | loss | dL/dw | dL/db | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 0.99 | 0 | 0.98 | -1.98 | -1.98 |

| 1 | 2 | 3.00 | 0 | 9.02 | -12.02 | -6.01 |

| 2 | 3 | 5.01 | 0 | 25.15 | -30.09 | -10.03 |

So \nabla \text{Loss}_{1:3} is

nabla = np.array([df["dL/dw"].mean(), df["dL/db"].mean()])

nabla array([-14.69, -6. ])so with \eta = 0.1 then \boldsymbol{\theta}_1 becomes

theta_1 = theta_0 - 0.1 * nabla

theta_1array([1.47, 0.6 ])| x | y | y_hat | loss | dL/dw | dL/db | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 0.99 | 2.07 | 1.17 | 2.16 | 2.16 |

| 1 | 2 | 3.00 | 3.54 | 0.29 | 2.14 | 1.07 |

| 2 | 3 | 5.01 | 5.01 | 0.00 | -0.04 | -0.01 |

So \nabla \text{Loss}_{1:3} is

nabla = np.array([df["dL/dw"].mean(), df["dL/db"].mean()])

nabla array([1.42, 1.07])so with \eta = 0.1 then \boldsymbol{\theta}_2 becomes

theta_2 = theta_1 - 0.1 * nabla

theta_2array([1.33, 0.49])